Torture Behind Closed Doors: The Abuse of Children at Lake Alice

This article contains descriptions of child abuse, electroshock treatment, medical misconduct, sexual and physical abuse, institutional neglect and psychological trauma and mental health.

In New Zealand’s North Island, once stood a rural psychiatric facility synonymous with trauma and systematic failure: Lake Alice. During the 1970s, children as young as nine were subjected to electric shocks, forced sedation and solitary confinement - not as treatment but as punishment. The Child and Adolescent Unit, overseen by Dr Selwyn Leeks, became a horrific site of abuse masked by medical authority and ignored by the state for decades.

362 children and young people went through Lake Alice between 1972 and 1978. However, that’s recorded numbers. Most of them had been wrongfully sent there from state-run welfare homes, and around half were Māori boys. Others were referred from the children's hospital units.

These children were wrongfully subjected to unmodified electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and paraldehyde injections as methods for punishment. They were also victims of sexual abuse.

The facility shut down in the mid-1990s and closed its doors in October 1999.

Only in the early 2000s did the Lake Alice survivors come forward about their stories. This fuelled a growing movement nationwide demanding recognition, justice and accountability for what happened to them as children. In the 2010s, the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care was established to investigate systemic mistreatment in state-run institutions. International bodies such as the UN Committee Against Torture condemned New Zealand’s slow response and failure to act on these allegations. In 2021, the Royal Commission launched a public hearing specifically focused on what happened at Lake Alice.

These are their stories.

Reminder - this article contains descriptions of child abuse, electroshock treatment, extreme cases of medical misconduct, sexual and physical abuse, institutional neglect, racism, colonisation, psychological trauma. Reader discretion is strongly advised for those who are sensitive to this content related to this.

Lake Alice Hospital opened in August 1950, it was largely self-sufficient with a farm, workshop, fire station, library bakery and laundry, and it had a swimming pool, glasshouse and gardens. Lake Alice was rejecting the ‘asylum model’ by housing patients in a series of ‘villas’. It was meant to create a more ‘home-like’ environment for patients and allowed a higher likelihood for recovery.

The gardens, farm, bakery and over facilities on the hospital grounds were not only to help the hospital be self-sufficient and supportive - it was also meant for hospital patients to be part of ‘useful labour’.

Lake Alice had a multi-disciplinary workforce consisting of psychologists, psychiatrists, medical officers, nursing staff, occupational therapists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, recreation officers, dentists and later on, teachers would also be staffed.

Many of them were locals from around Marton, and some were Mana Whenua from Ngã Wairiki and Ngãti Apa. Indigenous Maori people who have historic and territorial rights over the land.

The hospital was never meant for children, according to the medical superintendent at the time. They were avoiding admitting them ‘as far as possible’, yet 11 children were admitted in 1970. The annual reports from Lake Alice between 1970-1971 showed that 34 children and 59 youths spent time at the hospital.

Due to this, the Department of Education aimed for there to be a school and a children’s unit established due to the increasing number of youth and children being admitted. However, during the commission, the school had actually been at its lowest level of education and the students/patients were unable to make ‘normal progress in their studies’.

In 1972, the Child and Adolescent Unit was officially established under the leadership of Dr Selwyn Leeks.

The Royal Commission estimates that 400 and 450 children went through Lake Alice between 1970 and 1980. Only 362 children and young people were identified.

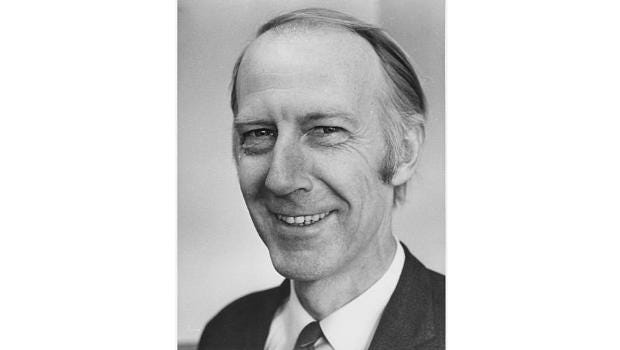

Dr Leeks was the senior psychiatrist and was considered the ‘architect’ of the cruel culture occurring at Lake Alice.

In 1971, the Palmerston North Hospital Board hired Dr Leeks as a child consultant psychiatrist and held this position until he left the country in 1977. He was the few ‘qualified’ child psychiatrists in New Zealand at the time.

Between 1953 and 1960, Dr Leeks completed his qualifications in science, medicine and surgery at the University of New Zealand.

From 1959 he worked in various medical, psychiatric and education jobs both in England and New Zeland. In 1969 he received a diploma of psychological medicine from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in London, and in 1971 he received a diploma in child psychiatry from the University of Otago.

Abuse at Lake Alice occurred because of him, John Blackmore and Howard Lawrence.

Dr Leeks malpracticed, perpetrated abuse and allowed it to happen. Dr Leeks, John Blackmore and Howard Lawrence created a power imbalance with doctors, medical staff and patients/children where sexual, physical and emotional abuse was allowed to happen.

According to the Department of Social Welfare, the median age range was 8 and 13 at the time of the unit opened. Survivors, however, have said there was younger children aged 4 or 5.

There were more boys than girls admitted to the Lake Alice unit.

The unit was intended to provide therapeutic care for children and adolescents with mental health issues, but the reality was that these children were not admitted for mental illness. They were referred for minor offences, general behavioural issues that all children go through and other social difficulties. Quite often, it was due to the children being of Māori descent and/or coming from a low socioeconomic background.

Racial discrimination played a significant role in what happened at Lake Alice. Māori children were disproportionately represented among those there and it wasn’t incidental - it reflected the broader systemic racism in New Zealand’s child welfare, education, health and justice systems during the 20th century.

According to to Department of Social Welfare the the Commission documents, there were 37% (recorded) Maori and/or Pacific children.

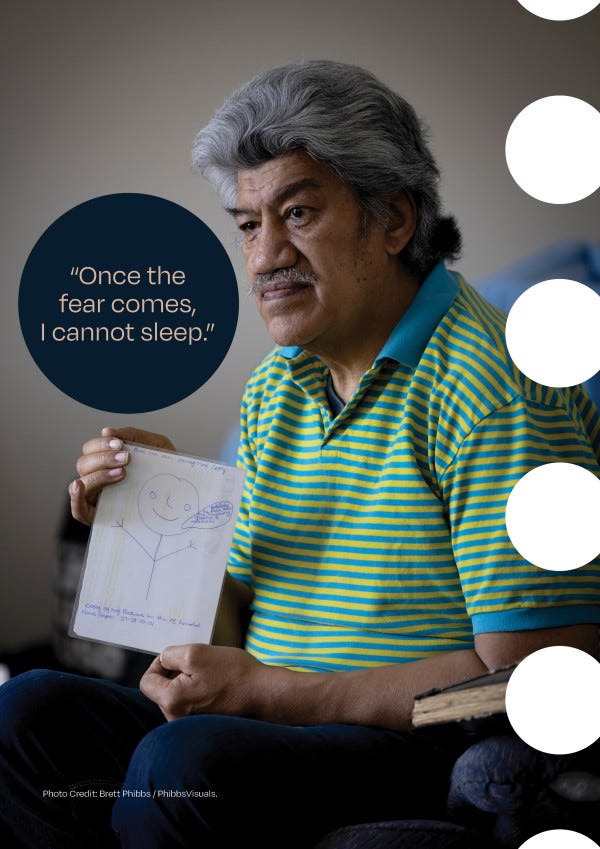

Mr Leota Scandlon, one of the Lake Alice survivors, said:

“The social worker told Dad that I needed a psychiatric evaluation because of the fights I was having at school. The social worker told him that they wanted to send me to Lake Alice Hospital. I knew my Dad couldn’t understand what they were saying because he couldn’t speak English. The social worker then gave me the phone to talk to Dad and I said to him in Samoan that I didn’t want to go to that place, being Lake Alice. I told him in Samoan because I didn’t want the Principal to understand what I was saying. Dad agreed to send me to Lake Alice. I was taken straight to Lake Alice from school by the social worker.”

Māori children were more likely to be removed from their families and placed in such psychiatric facilities, foster homes or ‘orphanages’ by state authorities. This was often due to truancy, poverty, family breakdown and other factors that tie into colonial disruption, socioeconomic marginalisation and the social issues occurring at this time.

Many of the Maori and Pacific Islander survivors reported that Lake Alice disregarded the Maori culture and didn’t let them access cultural learning while living there.

A survivor also reported that Maori boys were treated a lot worse than the other boys.

For children who had disabilities, families were misinformed and believed their children would get better care at the Lake Alice unit rather than at home. One survivor who had epilepsy said that his grandparents believed it would be ‘the best place’ for him to get help. Instead, those with disabilities and medical conditions experienced ableism at the unit. Many survivors reported that they were further discriminated against and they weren’t able to get the accessibility, additional support or accommodations required.

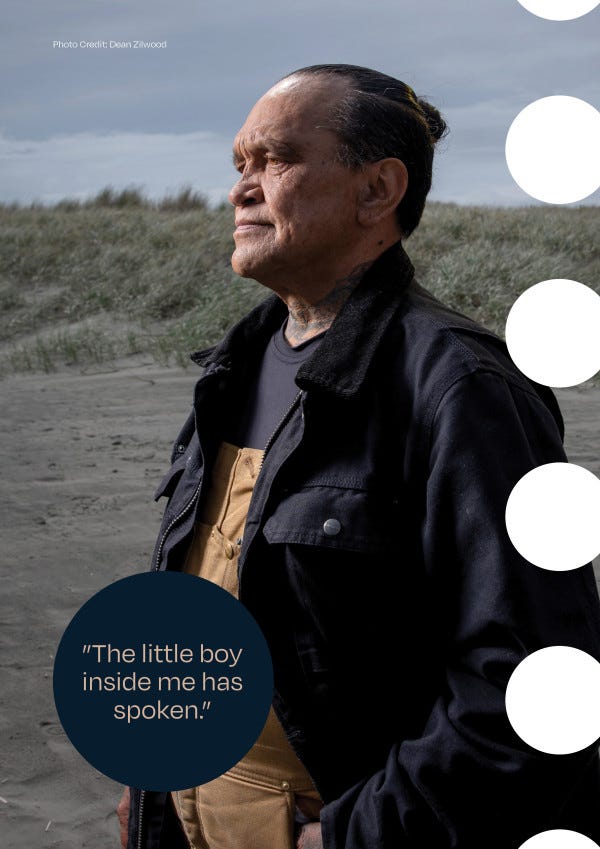

According to Hake Halo, they weren’t allowed to write home or contact their families.

He said that his mother tried to get them to stop, but she felt powerless as there was a language barrier - which was why he was placed in Lake Alice.

“There were no interpreters there and I was placed under guardianship. The social worker misunderstood my mother – she asked him to please look after me, while I was in care, but they thought she was saying to take me and make me a State ward. If a Niuean interpreter had been there, it would’ve changed a lot of things for me”.

Many of the children were misdiagnosed or wrongfully institutionalised without any legitimate psychiatric grounds. And this meant they were subject to extreme psychiatric treatments and abused through them.

A survivor, Ms Sunny Webster, told the Commission:

“I was diagnosed in Lake Alice with reactive depression, hysterical character disorder.[181] This is not what was wrong with me and the document proves that I was misdiagnosed. Nowhere on there does it say that I was a victim of sexual abuse, and that was the problem.”

Most children were also admitted to Lake Alice as they were ‘very vulnerable, seriously disturbed and in need of care and protection’.

But this wasn’t the case.

At Lake Alice, unmodified electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was routinely administered to children without anesthesia or muscle relaxants. ECT was typically reserved for treating severe depression or psychosis under controlled conditions. However, at Lake Alice, it wasn’t used as therapy but as a form of punishment for perceived misbehaviour such as bedwetting, swearing, bad grades, or not following orders like eating vegetables. ECT would be dialled up to higher settings and without modifications such as anesthesia and muscle relaxants.

Electrodes were applied not only to the head, but also genitals, inflicting severe pain and psychological trauma. One survivor described the experience as being ‘electrocuted like a dog’.

Another common method of punishment was the use of paraldehyde - a painful and powerful sedative. Children were injected in the buttocks without medical justification and patient consent. These injections were used indiscriminately and routinely in response to complaints or resistance to staff orders.

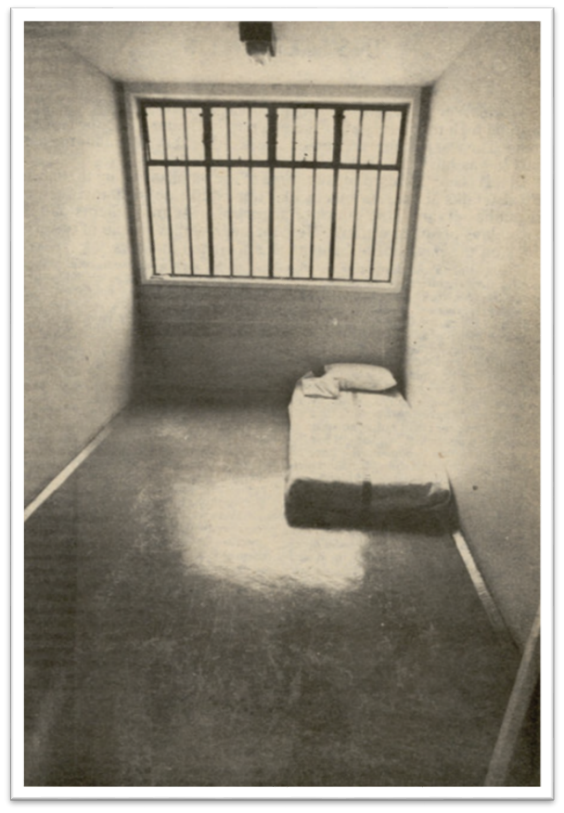

Solitary confinement was another tool of control where children were locked in bare seclusion rooms for hours or even days, then immediately subjected to ECT. These rooms were devoid of comfort or stimulation and were intended to isolate children from any sense of safety or support.

From ‘The Lake’ Podcast - survivors talked about this in detail about the severity of the treatment and how they were abused through these methods. One of them even said they no longer eat vegetables because they were constantly shocked for not eating ‘properly’.

Kids were also beaten and mistreated heavily by staff. Survivors told the commission that they experienced physical abuse in the unit.

They were ‘thrown around’ and there was even a designated ‘boot room’ where staff could physically assault the children.

“I was punched in the back of the neck and kicked by two staff. Other patients were roughly treated in there. It was quite obvious as the staff would start on them in the day room and from there take them to the boot room. It could be heard and was talked about.”

Skip if you need - it’s about sexual abuse and there are quotes

Sexual abuse was common at the unit. Ms Collis reported that Mr Leeks raped her during her stay at the unit and that she was drugged. She had complained to staff and one nurse told her, ‘it was her imagination’. She had given up on telling her story to staff and trying to get help.

“Sometimes it was before the nurse would get to me and rape me also. I was so ashamed and embarrassed about what was happening to me sexually, and this embarrassment and shame has stayed with me my whole life. These are horrific memories to live with.”[645]

Survivors described being targeted in their beds by staff both at the unit and at the villa accommodation. Several survivors said that they were assaulted after ECT or after receiving injections.

Another unconscious victim from the ECT recalled his experiences:

“I have flashbacks of this but no clear view of the person. I was left in the cell after an ECT for two or three days, cold, naked with one blanket and a bucket for a toilet”.

Many survivors also told the Commission about the abuse occurring among peers and how the hospital administration refused to keep them safe or create preventative measures.

Dr Leeks had even prescribed contraceptives to female patients to ‘avoid an unwanted pregnancy’ from their abuse.

The Commission found that there was no evidence to suggest staff took steps to investigate the allegations of abuse occurring during Lake Alice Hospital’s operation. The sexual abuse was undoubtedly pervasive and committed by adult staff members and patients. John Blackmore and Howard Lawrence were these staff members.

Blackmore had sexually assaulted multiple patients.

Lawrence would even threaten to kill the children if they didn’t obey orders. He also sexually assaulted many patients.

If staff spoke up, their jobs were threatened, and so was their safety and well-being. Quite often if they did go above and beyond Lake Alice to report, they were ignored.

Dr Leeks had a ‘demand and obey’ approach with staff and patients and had created a culture between staff and patients that was anything but therapeutic but more negative. As if he wanted them to also abuse the children as he and other staff would do.

According to a survivor:

“as a kid I couldn’t tell if they were good or bad but they seemed alright. It was only later in life that I realise, looking back, that some of the staff at Lake Alice were corrupt and caused a lot of harm to the kids there”.

“A lot of the male staff were horrible, but Nurse Leonard was lovely and kind and like a mother to us. Mrs Duncan the cook was also lovely and would mother us children. Some of the female staff were lovely, they would give us lollies, kisses, and awhi. Some of the male staff found every opportunity to laugh at us and make fun of us … As children we were told by the male nurses that there were men with guns in the towers and that if we ran away, we would be shot. I believed that.”

The Commission had received statements from Lake Alice school staff who were employed between 1973-1978. Many of them supported the claims of abuse and how other staff were coerced into abusing or mistreating children.

“I’m pretty sure the ‘zapper’ was always talked about in terms of punishment because I remember the guards making threats to the kids in the classroom, such as watch yourself or you’ll get the zapper (ECT)”.

Teachers were also forced to grade on a ‘behaviour modification system’ - such as giving students lower or higher grades based on behaviour which would indicate ‘which child needed to be punished’.

Survivors experienced homophobic and transphobic abuse at the unit. Homosexuality or behaviour and attitudes not considered ‘normal’ were to be ‘treated’.

Evidence shows that Dr Leeks believed that sexual identity could be determined at an early stage and could be ‘reversible’.

In 1972, this sick, twisted individual wrote (about an underage patient)

“As regard to his homosexual trends, these may not be reversible as one’s sexual identity is determined from a fairly early age and added to within the first five to seven years of life. Subsequent events only emphasise that which was already there”.

He was also allegedly trying to do conversation therapy practices. He used aversion therapy and had even involved NZ Police if the children were leaving the unit so they could ‘keep an eye on them’.

Dr Leeks also knew about other sexual abuse occurring from staff to child patients. Instead of reporting or identifying the abuse, he referred to the incidents being ‘consensual / experimental homosexual acts/behaviours’ rather than seeing it for was it was - child abuse and rape.

One survivor said he and another patient were called homophobic and transphobic slurs by staff and patients. They told the Commission that staff and patients “constantly ridiculed” a female patient because of her intersex status.

From the moment the Lake Alice Hospital and the Child and Adolescent Unit opened, patients and staff had made complaints, but their stories were dismissed and disbelieved. Complaints about Lake Alice were raised with the Department of Social Welfare about the unit from as early as 1972 and 1973.

There is a brief timeline of the issues occurring at Lake Alice:

Mr Brian Paltridge, was jailed in December 1972 for indecently assaulting a boy in the unit.

In January 1973 the first complaint of abuse is reported to the Department of Social Welfare by a boy who was sent there.

In November 1974, acting chief educational psychologist Don Brown raised concerns with Dr Sydney Pugmire about the improper use of ECT at the unit.

In January 1976 the CCHR (Citizens Commission on Human Rights) toured the hipsital and raised concern about the placement and treatment of care for the children.

Parents of a boy sent to the Lake Alice children’s unit complained to the Ombudsmen in 1976.

There are multiple red flags raised throughout the 70s from inquiries to complaints. Including an investigation into the complaint made against Dr Leeks in 1977 - they find him ‘not upholding of the complaint’.

Despite complaints made to NZ Police and Medical Associations, Dr Leeks leaves New Zealand for Australia with a ‘good standing’. NZ Police even decided not to prosecute or investigate further.

By 1980 the unit closed.

In the 1990s and 2000s more survivors came forward, including Malcolm Richards who played a crucial role in exposing the abuse occurring at Lake Alice through media interviews and testimonies.

He expressed anger about the redress:

"No way I'm taking part in it because it's not legal. We can't allow the perpetrator of this crime, which is the government, to set their own sentence."

Throughout the 2000s NZ Police and the Medical Council received multiple complaints, but these investigations were slow, closed without charges and incomplete. The effort to prosecute Dr Leeks was also dropped because of his ‘age and health’ (ridiculous) (he died thank god).

In 2019, the United Nations Committee Against Torture condemned New Zealand for its failure to adequately investigate the allegations surrounding Lake Alice and called for an independent inquiry. This criticism put significant international pressure on the government to take action and brought new attention to the long-ignored survivors.

In 2021, the Commission held public hearings specifically focused on Lake Alice, giving survivors a national platform to tell their stories under oath.

The Royal Commission found overwhelming evidence of systemic abuse, medical misconduct, and state negligence. It condemned the New Zealand government, police, and medical authorities for failing to protect children and ignoring repeated warnings. The government and police eventually issued formal apologies, and some survivors received compensation, although many argue it remains inadequate.

The impact of the abuse was extreme as you can imagine. Many survivors Many survivors have come forward were were part of Abuse in Care Royal Commission have reported that their physical, emotional, cultural and spiritual health and wellbeing have been extremely affected.

Many of them have gone through traumatic experiences that have affected every apsect of their lives. Some have had experiences with law enforcement after their time at Lake Alice, some have struggled with employment and further education. Many have found hope and received the adequate care and treatment needed for their mental and physical health.

One of them, Bryon Nicol quoted that “for me, the inquiry was about a proper apology from the Government and to make sure it never happens again to another child”.

Main Sources:

https://www.abuseincare.org.nz/reports/inquiry-into-the-lake-alice-child-and-adolescent-unit/conclusion/endnotes#A50

https://www.abuseincare.org.nz/reports/inquiry-into-the-lake-alice-child-and-adolescent-unit/2-1-what-happened-at-lake-alice/2-1-what-happened-at-lake-alice

https://www.abuseincare.org.nz/reports/inquiry-into-the-lake-alice-child-and-adolescent-unit/executive-summary/timeline

https://www.abuseincare.org.nz/reports/inquiry-into-the-lake-alice-child-and-adolescent-unit/2-1-what-happened-at-lake-alice/hake-halo

‘The Lake’ Podcast by Stuff Audio and Popsock Media