The Retta Dixon Home and the Echoes of Injustice

Content warning: this article discusses topics including child abuse, sexual abuse, forced removal of children, and systemic neglect of Indigenous Australians.

Further CW: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following content contains references to the Stolen Generations, institutional child removal, and accounts of mistreatment, neglect, and trauma experienced by Indigenous children and families. It also discusses the experiences of survivors of the Retta Dixon Home. It may also contain images or names of people who have passed away.

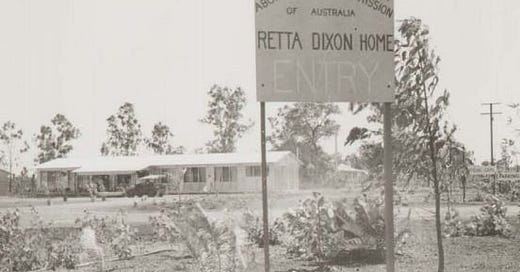

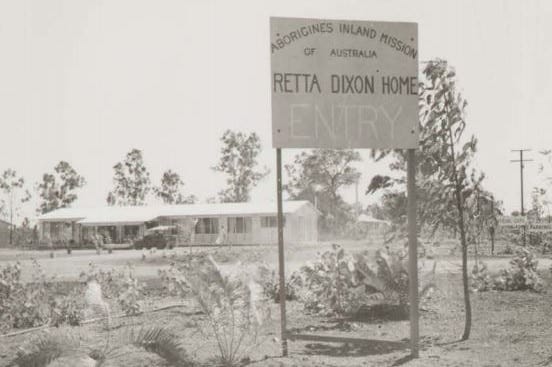

Tucked behind the tropical facade of Darwin lies the haunting memory of a place that holds deep scars for many Aboriginal Australians - the Retta Dixon Home.

The Retta Dixon Home was established at Bagot Road in 1946 by the Aborigines Inland Mission (AIM). It was an ‘institution’ for Aborignal children and mothers and was run in conjunction with a ‘hostel’. It was in charge of a number of Aboriginal women and children who were referred to as ‘part-coloured’ or ‘half-caste’.

In reality, the Retta Dixon Home was a symbol of forced removal, cultural erasure and unchecked abuse. Generations of children were torn from their families, subjected to harsh discipline, exploitation and in many cases, physical and sexual violence.

It was part of the wider policy of assimilation - a systematic effort to remove Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families to ‘civilise and integrate them’ into a white Australian society.

The Retta Dixon Home was in operation until 1982.

The Retta Dixon Home became the subject of a royal commission, which uncovered the harrowing testimonies of sexual and physical abuse perpetrated by staff members.

In 2015, a class action was launched by 85 former residents seeking redress for the abuses they endured. This led to a settlement in 2017, marking a pivotal moment in acknowledging the suffering of survivors.

To this day, many survivors continue to advocate for formal apologies and broader recognition of the injustices they faced.

AIM still operates today but has changed its name to Australian Indigenous Ministries.

The Retta Dixon Home was established as a ‘home’ for half-caste children and mothers as well as a ‘hostel’ for young half-caste women. In December 1947, the home was granted a licence by the Australian Government to be conducted as an ‘institution’ for ‘the maintenance, custody and care of aboriginal and half-caste children’.

The Australian Government was the guardian of many children at the Retta Dixon Home. The government had general responsibility of all children at the home.

In September 1947, six staff members worked in the Home under the direction of Miss Shankelton. By March 1949, the number of children at the Home had increased to 67.

A 1950 Review Report on the Retta Dixon Home said the average yearly number of children at the Home was 70 and that the average number of women receiving pre-natal and aftercare was eight.

Children stayed at the Home until they were 18 years of age. They attended school from 5 to 16 years, and after leaving, were expected to do vocational training.

Many of the children brought to Retta Dixon were victims of the Stolen Generations, taken from their families without consent under legislation that deemed Indigenous families unfit to care for their own. At Retta Dixon, these children were subjected to strict discipline, cultural disconnection an,d as later investigations and survivor testimonies revealed, widespread sexual and physical violence perpetrated by staff.

Many of the children who were at Retta Dixon would then be sent interstate to complete their schooling as part of the Part-Aboriginal Education Scheme.

In 1951 the Retta Dixon Home cared for 70 children and up to 20 women in what was referred to at the time as “crowded” conditions.

The Retta Dixon buildings were made up of a nursery, staff quarters, a girls’ dormitory, a boys’ dormitory, a young women’s quarters, a recreation room and a ablution block. No traditional songs, dances or ceremonies were allowed and they were highly discouraged.

Over the years 1954 to 1957, the Northern Territory Government assisted the AIM with some major purchases such as a Bedford Truck and later a VW Combi Van for transporting children, a refrigerator, the construction of a tennis court and poultry run and the provision of sixty individual bedside lockers.

In 1956, 47 boys and 34 boys were ‘committed’ to the Home and 6 women were in residence.

During these years, concerns about the conditions of the home came into focus. However, these concerns were ignored.

In 1955 the Director of Welfare, Harry Giese, stated in a letter that because the majority of children at the Retta Dixon Home were wards of the state, he as Director, should have ‘a strong say in what liberties should be granted to the children when they approach the age where they will (need) to undertake their own responsibilities.’ This meant that children should become part of external community groups such as Girl and Boy Guides / Scouts and Police clubs etc.

In 1947, the Retta Dixon Home was impacted by Cyclone Tracy, leaving the buildings in ruins and 50 children had to be sent interstate ‘temporarily’.

Due to this, the decision was made to close the home amongst other reasons such as funding.

It’s important to note that throughout the operation of the Retta Dixon Home, it was run by a religious organisation that had limited government oversight.

Survivors recalled that Retta Dixon was governed with strict rules and had rigid discipline where children and young women were expected to follow detailed rules about how to behave, speak and even express themselves. If these rules were broken, punishment was followed.

These experiences left many children feeling anxious and constantly afraid of doing the wrong thing. For children already dealing with the trauma of family separation, this environment only deepened their distress.

Even when it came to reporting the abuse they were facing.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, several residents told Mr Mervyn Pattlemore, the superintendent at the time, that they were being sexually abused. Despite given evidence, Pattlemore didn’t believe them and caned them for lying.

Even when staff came forward, Pattlemore didn’t investigate or dismiss those perpetrators who were named. He ignored all of them.

In 1973, the girls at the home told a house parent that Mr Donald Henderson had been sexually abusing boys at the time. Despite the house parent reporting to the superintendent, Pattlemore, Henderson stayed on.

It was only in 1975 that Henderston was charged with seven sexual offences. Yet none of the charges proceeded to trial, and Henderston wasn’t convicted.

In 1966 a house parent, Mr Reginald Powell, was prosecuted and pleaded guilty to sexual offences against children at the home.

In 1998 a former resident of the home made a complaint to the police about Henderson. In 2001 charges were laid against Henderston by the NT Police in relation to the abuse.

On 22 March 2002 Mr Henderson was arraigned in the Supreme Court on 15 counts. He pleaded not guilty.

On 7 November 2002, a senior prosecutor at the DPP, Mr Michael Carey, recommended that the prosecution be discontinued on the basis that there were no reasonable prospects of conviction.

On 11 November 2002, a nolle prosequi was entered on all charges and the prosecution was discontinued. The DPP did not notify the victims or the officer in charge of the investigation, Detective Roger Newman, of the decision until 27 November 2002.

During the commission, several Retta Dixon Home former residents gave evidence.

One woman was removed from her family and taken to Retta Dixon Home while Shankleton was superintendent. The same woman reported that children would be flogged for speaking in their native language or chained to their beds with a dog chains / leads.

According to a former resident, Mr and Mrs Walter had played a role in sexually assaulting children, Mrs Walter defending her husband, Desmond, and turning a blind eye to any complaints made by the children.

Another resident stated that Mr George Pounder would chain the children to their beds and ‘sniff them’. He would insist on driving certain children to school and would touch them without their consent.

Mr Pounder was never charged with any criminal offence. He thankfully died in 2014.

Another woman was given to Retta Dixon Home by her father under the legislation, she reported being belted by Miss Judy Fergusson when she wet the bed. She had humiliated her publicly and had stabbed another child with a can opener.

In addition for caring for children, the Retta Dixion Home also housed young Indigenous women, mostly teenage girls and mothers with infants. Many of them had been removed from their families under Stolen Generation Policies and had been sent to Retta Dixon Home as part of assimilation.

Some young women who became pregnant — often through coercion or assault — gave birth while still living at Retta Dixon. In many cases, their babies were taken away shortly after birth, sometimes placed in the same institution or sent elsewhere. The Royal Commission heard evidence that some mothers were discouraged or prevented from forming strong bonds with their children, a practice that reflected broader policies of separating Aboriginal families.

There was little to no support provided to these young mothers. They often lacked access to appropriate medical care, emotional support, or parenting guidance. Many later described the heartbreak of being treated not as mothers, but as burdens or failures.

From an early age, these girls were expected to take on domestic roles, this labour was framed as ‘training’, but it was indeed slavery.

For many survivors, the effects of their time at Retta Dixon have lasted a lifetime. The experiences of separation, loss, and institutionalisation have left emotional and psychological scars. Some survivors have described ongoing struggles with confidence, relationships, and a sense of belonging.

The Royal Commission into the Institutional Responses of Child Sexual Abuse examined Retta Dixon Home. The hearing was held between September and October 2014.

The commission heard evidence and named the perpetrators - Mr Desmond Walter, Mr George Pounder, Miss Judy Fergusson and Mr Donald Henderson and Mervyn Pattlemore for his negligence.

The commission revealed that reports of abuse were often inadequately addressed by the institution's management and relevant authorities. For instance, while some allegations led to convictions, such as that of Mr. Powell in 1966, other reports, including those against Mr. Henderson in the 1970s, were not effectively acted upon.

AIM accepts that from 1947 until 1980, when the Retta Dixon Home operated, AIM did not provide training to persons who worked at the home on how to detect or respond to child sexual abuse.

In 2021, the Commonwealth government has agreed to be a funder of last resort for this institution. This means that although the institution is now defunct, it is participating in the National Redress Scheme, and the government has agreed to pay the institution’s share of costs of providing redress to a person (as long as the government is found to be equally responsible for the abuse a person experienced).

The Royal Commission's findings underscored the lasting impact of the abuse on survivors. While some redress efforts have been made, including compensation schemes, many survivors continue to seek formal apologies and recognition of the injustices they endured. The case of the Retta Dixon Home serves as a poignant reminder of the need for vigilant safeguarding measures and accountability within institutions responsible for the care of children.

If you need support, please contact:

13YARN – 13 92 76 (24/7 crisis support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people)

Lifeline – 13 11 14 (24/7 crisis support and suicide prevention)

The Healing Foundation – Support for Stolen Generations survivors and their families