A call comes in just after 7am.

A panicked young man, voice trembling tells the emergency operator:

“They’re all dead. My family. They’re all dead”.

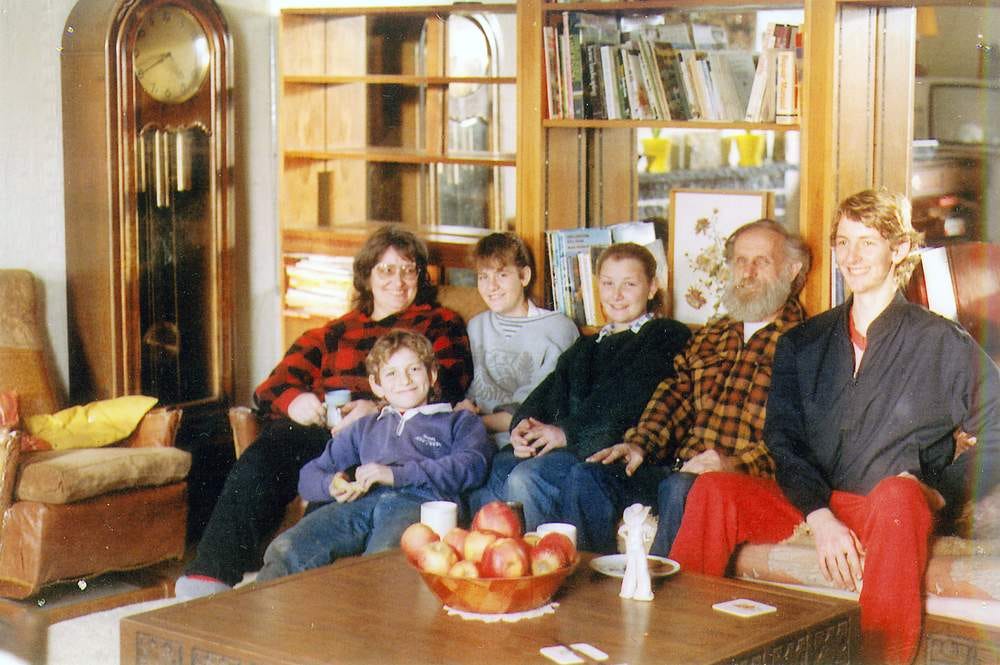

On the morning of June 20, 1994, police in Dunedin, New Zealand responded to a distressing 111 call from a young man named David Bain. What they discovered shocked the nation: five members of the Bain family - Robin (58), Margaret (50), Arawa (19), Laniet (18) and Stephen (14) - were found dead in their home. It was an unimaginable horror, five members of the Bain family were shot dead in their own home.

A computer screen at the scene displayed a chilling message:

“Sorry, you are the only one who deserved to stay”.

The only survivor and eldest son, David, survived. Was David simply a devastated survivor of his father’s murderous rampage - or was he the cold blooded killer who wiped out his family before calling police?

What followed was one of the most controversial and heavily debated criminal cases in New Zealand’s history, a saga that involved allegations of parricide, a botched investigation, claims of innocence and a divided public.

The Bain family lived in Dunedin, New Zealand’s South Island, and consisted of Robin and Margaret and their four children: David, Arawa, Laniet and Stephen. On the surface they appeared to be a quiet, middle-class family - but behind close doors, tensions were simmering.

Robin and Margaret married in 1969, both of them are educated, religious and idealistic. As a couple, they shared a strong religious foundation early on.

Robin, the father and a school principal, was 58 when he died. He had spent time working in Papua New Guinea as a missionary and teacher, a role that aligned with his strong religious beliefs. When he returned back to New Zealand after living and working in PNG for quite some time, he had experienced personal and professional difficulties. He was living in a caravan on the family property, separated from Margaret but residing at the family home.

Margaret, the mother, was deeply involved in spiritual and alternative beliefs. She was increasingly reclusive and had become interested in esoteric and New Age philosophies. Friends and family noted that her mental health seemed to deteriorate over time, and she had written strange letters and notes expressing grandiose ideas and prophecies.

During the 1970s and 1980s, they had moved together to PNG, where Robin was working as a missionary and teacher in remote areas. However, while there, the living conditions for the young family were isolated and they found it difficult. Some sources suggested that this was what led to Robin being emotionally withdrawn and Margaret’s mental health declining.

Margaret and Robin’s marriage was troubled. They lived very separate lives and there were tensions over parenting, religious and spiritual differences and how the household was run.

David, 22 at the time, was the eldest and only survivor; he was studying music and drama at the University of Otago. He was known as quiet and intellectual and always involved in community theatre and amateur dramatics. He lived at home and helped with household responsibilities. He was seen as odd; he was still doing a paper route at 22, he had previously failed at university and didn’t have many friends.

David appeared to live a relatively normal life, but during the trial the Crown painted him as emotionally troubled and jealous. Some people who defend him argue he was a devoted son and brother who was wrongly accused and unfairly portrayed.

Arawa Bain, 19, was the second eldest; she was known for being responsible and caring. She had ambitions to become a teacher and was seen as the peacemaker in the family. Friends described her as a friendly, sensible and mature person.

Laniet Bain, 18, had a more complicated relationship with her family. She had moved out for periods and had been known as outspoken. Reports suggested that she had accused her father of sexual abuse - a claim that would become central to the defence at David’s trial. Laniet had also been involved in sex work, which, according to court records, may have contributed to the familial tensions.

Stephen Bain, 14, the youngest child, was still in high school. He was sporty, energetic and popular among his peers. Evidence from the crime scene suggested that Stephen fought back against his attacker, and his struggle was one of the most violent aspects of the family murders.

The Bain family home was described as chaotic and emotionally charged in the years leading up to the killings, particularly between the parents and their roles in creating a volatile environment.

Margaret had referred to Robin as “one of the Four Crown Princes of Hell”. She had apparently told people she would shoot him if she could.

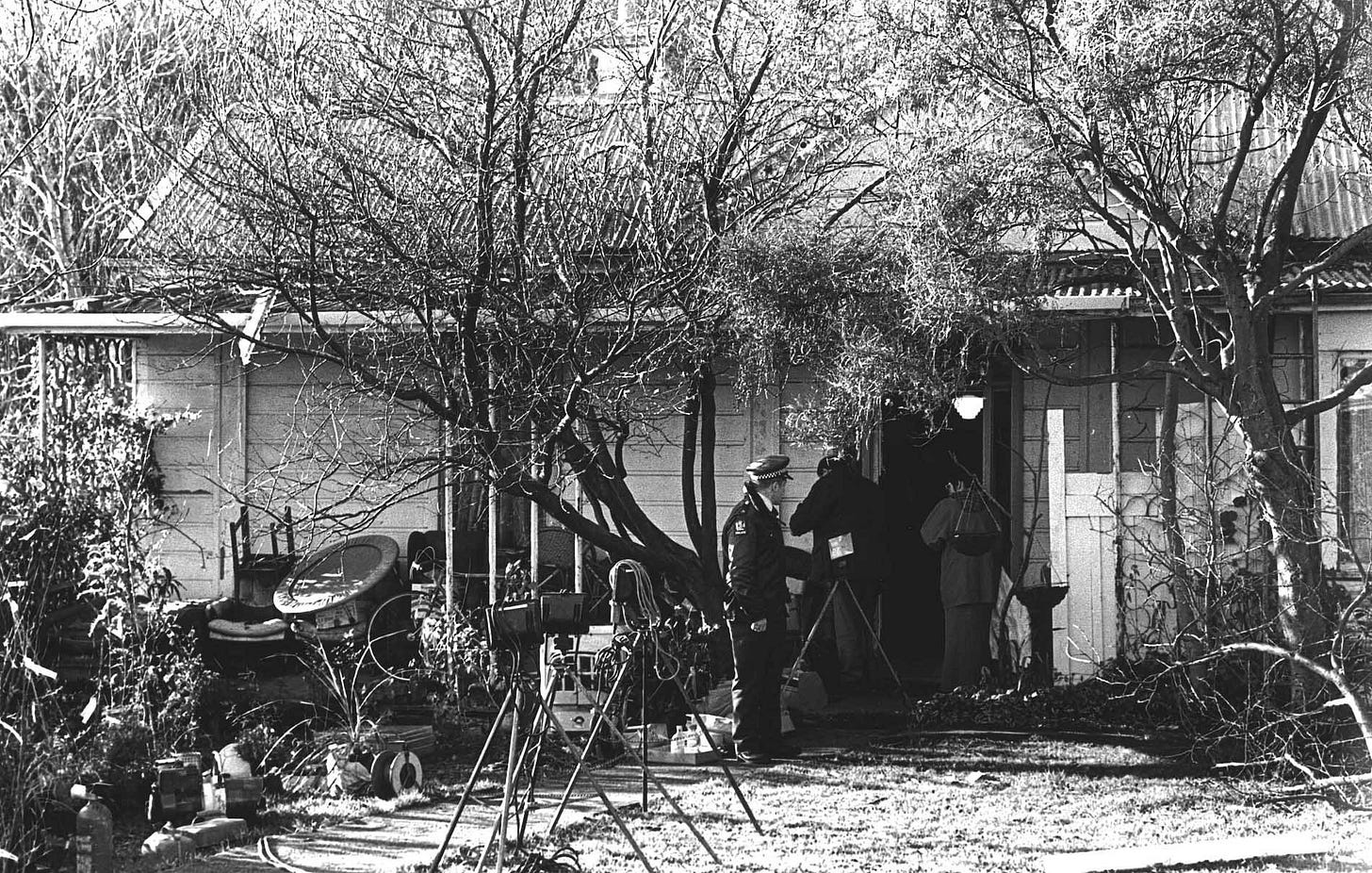

The family home at 65 Every Street, Andersons Bay, Dunedin was described as ‘semi-derelict’. Photographs presented at the trial had showed that most of the rooms were messy with family belongings all over the place in disorderly heaps.

Several witnesses testified to strange behaviours, mental health issues and interpersonal conflict.

Robin was ‘deeply depressed on the point of impairing his ability to do his job of teaching children’. He would often sleep in the back of his van near the Taieri School, where he worked, and when he came home on weekends, he would sleep in a caravan on the property.

The Final Days

In the days leading up to the murders, the household becomes extremely unstable.

Laniet has moved back home. According to testimonies from friends and thee defence, she had confided in others that she planned to confront the family and go public and “come clean” about the alleged sexual abuse she suffered at the hands of Robin.

This was supposed to happen on Sunday night 19th of June - the evening before the murders.

Some accounts suggest that Margaret Bain was growing more erratic in her behaviour, adhering obsessively to spiritual routines and asserting mystical beliefs about her children’s destinies.

Meanwhile, Robin was still sleeping in the caravan on the property and had returned home that weekend, as he often did.

The Day of the Murders

At 5:45 am, Monday, June 20th 1994, David reportedly begins his paper route, which he regularly completed in 60-70 minutes. He collects newspapers from a depot and begins delivering them by bicycle across his route in the Dunedin suburbs.

Witnesses recalled seeing David on his route that morning behaving calmly. One women said he was paused to talk with her about her dog.

Approximately around 6:40-6:50 am is when the murders are believed to have occurred based on testimony and forensic estimates. All families were shot with a .22 calibre rifle. There were no signs of forced entry and the killings appeared to be targeted and methodical.

Margaret Bain is found dead in her bed.

Arawa is found in her bedroom, shot and possibly awake when attacked.

Stephen, the youngest, appears to have fought his attacker violently. His body is found in a bloodied room, with signs of a struggle. There was blood smeared on the walls and his clothing was torn, his body briised.

Laniet is found with multiple gunshot wounds, including one through the cheek and one to the head. She was shot three times at close range. Experts said that multiple shots implied a calculated turen - not consistent with an impulsive act.

Robin Bain is found in the lounge next to the computer. He is shot in the head, and the rifle is lying next to him. There is no blood spatter or residue on his hands — a detail that would later become crucial.

At 6:44-6:56 am, someone logs onto the Bain household computer. The message is typed and left on the screen:

Sorry, you are the only one who deserved to stay

Prosecution would later argue that David typed it before calling emergency services.

The defence would claim that Robin may have done this as part of a murder-suicide.

At 7:09 am, David comes home around this time supposedly and then calls 111 telling the operator - “they’re all dead. My family. They’re all dead”.

When officers enter the house, they find David in a state of shock, wearing his bloodstained clothing. He was then taken away for questioning and later to the hospital, reportedly in a distressed state.

Within hours of escorting David to the hospital, where he was assessed, questioned and later released, officers realised something wasn’t adding up.

The Investigation

Although the crime initially appeared to be a murder-suicide, with Robin Bain as the likely perpetrator, forensic anomalies began to challenge that assumption.

The .22 rifle that was used in the killings belonged to the family, and it had David’s fingerprints on it right where they would be placed for loading and firing. How the bodies were found, the state as well as other forensic findings, indicated that there was no way Robin Bain could have committed a murder-suicide.

David had told police his version of events - he returned home from his morning newspaper run at 6:55 am to find the house eerily quiet, then he found his family dead and called emergency services.

Investigators reconstructed David’s paper route, and it appeared to them that David completed it faster than usual - suggesting that he could have had time to commit the murders before leaving or to return during the run and then continue on as if nothing happened.

David told police he had checked on his family and tried to perform CPR. However, forensic experts noted that there was little to no blood transfer consistent with his story. Even though his clothes were stained, they weren’t stained in a way that matched attempted resuscitation.

The glasses David usually wore were also broken. The lenses from them were found in Stephen’s room, one hidden under the bed. This really indicated that David had them on during the struggle and that there were knocked off.

Linking him in a direct conflict with Stephen.

Over the next few days, the initial theory of murder-suicide begins to crumble under the weight of forensic inconsistencies and David’s own shifting account. By the end of the week, detectives were zeroing on him.

On June 24th, 1994, just four days after the killings, David Bain was arrested and charged with the murder of his entire family.

Investigators believed that David carefully orchestrated the killings to make it look like his father had snapped, therefore staging the computer message suicide note to implicate Robin.

David’s timing, behaviour and physical evidence at the scene all fed into what became the Crown’s central theory: David killed his family before his paper route.

But David’s defence would argue that the same evidence pointed to Robin Bane - a broken father and husband, driven by shame, religious mania and the threat of exposure.

The Trial of David Bain

On June 24, 1994, David was charged with five counts of murder, which left New Zealand stunned. One moment, he was a traumatised survivor; the next, he was at the centre of a chilling familicide.

His 1995 trial at the High Court of Dunedin would become one of the most controversial and high-profile cases in New Zealand’s history.

Prosecutors would argue that David meticulously planned the murders by waking up early, donning gloves and using the family’s rifle to shoot his parents and siblings before going on his paper run. A routine that he used to create an alibi.

Their narrative was built on several key points:

The computer message was typed while David was home, not Robin

David’s bloody fingerprints were on the rifle

His damaged glasses were found in Stephen’s room, suggesting a violent struggle

The crime scene showed signs of staging - with Robin’s apparant suicide inconsistent with the lack of blood splatter, gun residue and bullet trajectory

The victims were shot in a sequence that suggested knowledge oft the house and a personal vendetta - not rage.

David’s defence had painted a different picture: Robin Bain, a mentally disturbed and broken man, as the killer.

The defence’s key points included:

Robin was depressed, isolated and living in a caravan and heavily estranged from his family

He had allegedly sexually abused Laniet throughout her childhood. She had also threatened to expose him

The message on the computer was typed out by Robin

David returned home later after the murders occurred

There was no motive for David to kill his entire family

Unlike most murder cases, the Bain case had no financial incentive, no romantic trigger or external conflict. Which would lead to the prosecution building motive around pscyhological factors and family dynamics.

According to the prosecution, David Bain’s motive for murdering his family had to be a mix of resentment, control and emotional instability, particularly in a dysfunctional household. They argued that David felt trapped living at home with his two parents, who were becoming more domineering and emotionally distant and putting pressure on him.

The Crown also suggested there was possibly a power struggle between David and Robin.

They constructed the idea that David envied his father’s role as the patriarch of the family and felt pushed aside. There were also allegations that David wanted to be head of the household and saw Robin as a weak, fallen male figure who no longer deserved that position - especially with accusations of sexual abuse, including Laniet. He may have harboured delusions of control or possibly hero fantasies. This theory was bolstered by his strangely calm demeanour during parts of this paper run and after the emergency call.

Then there was another theory, David wanted to kill everyone in order to ‘save’ his family from a shameful scandal - Laniet’s abuse.

Critics argued, including David’s supporters, that the prosecution’s motive was highly speculative, vague and circumstantial.

Also it was hard to determine what happened with Laniet’s abuse and whether this was a motive because a witness who was called to testify didn’t turn up. Although she did provide a written statement, the Justice presiding the case found it unreliable. So whether Laniet intended to disclose allegations of incest against her father before the killings was not presented to the trial jury.

Despite this, the jury then delivers a guilty verdict on the five counts of murder.

David Bian was sentenced to life in prison with a 16-year non-parole period.

But this was far from the end of the story.

The Bain House Burning

In 1996, the Bain family home on 65 Every Street, the site of the massacre, it burnt down by Dunedin City Council and at the request of other family members.

Officially, it was said to burnt due to safety concerns and the decaying condition of the property. Many also believed that it was done in the desire to erase the horrors, and to stop the house from becoming a morbid tourist attraction.

However, the destruction of the home had eliminated a critical crime scene.

A Retrial and Botched Investigation Claims

Yearrs later, as appeals mounted, attention turned to the police investigation which was becoming criticised for serious flaws and oversights. A 2007 report by the NZ Justice Ministry and the Privy Council (UK) highlighted multiple issues.

Major concerns included:

Contamination of evidence

Police walked through the scene before it was properly secured

Failure to test Robin’s hands properly for gunshot residue

Forensic Mishandling

The sequence of murders, movement of bodies and location of key items (the glasses) weren’t properly preserved or photographed

The computer’s boot-up time was not verified accurately (it was a 90s computer thing)

Detectives may have been biased towards David

Therefore ignoring evidence that pointed to Robin

The Privy Council later quoted:

“Their Lordships are clearly of the opinion that the fresh evidence adduced in support of the appeal, taken together with the evidence given at the trial, comples the conclusion that a substantial miscarriage of justice has actually occured” 2007

This ruling quashed the 1995 convictions and led to his 2009 retrial.

In March, 2009, after serving 13 years in prison, David Bain stood again on the dock. This time with a new defence team, in a new city and a dramatically shifted public mood.

Throughout the early 2000s there was growing unease about the fairness of the original trial. The public felt that the original conviction was flawed and the Privy Council’s declaration in 2007 really undermined their confidence in the system.

Another major factor was Joe Karam’s role in advocating for David. Joe was a former All-Black player turned justice campaginer who investigated the case independently, including writing books, appearing on talk shows and interviews to talk about it and even raised funds for legal effort with David’s appeal.

The tone of media changed, David was framed as soft-spoken and intelligent man who had spent his 20s and 30s behind bars. The media begun to publicise his quiet demeanor and his apparent emotional fragility and trauma. This created a public shift with their attitudes towards him.

The retrial lasted more than three months in Christchruch. It became one of the longest and most expensive trials in NZ’s legal history.

At the heart of it was a simple question - Had David Bain murdered his entire family? Or had he been imprisoned for a crime committed by his own father?

David’s new legal team, led by Michael Reed QC and supported by a long time advocate Joe Karam, mounted a far more aggressive defence than the 1995 trial. The strategy was to c completely dismantle the Crown’s case by reframing Robin as the real killer.

The defence argued that Robin Bain was deeply disturbed and a deterioratign man who was sleeping in a cold, squalid caravan on the family property and was estranged from his wife and children. They further argued that Robin did sexually abuse his daughter and that he was triggered as she threatened to go public with her allegations.

Forensic experts even testified that Robin may have committed suicide based on the trajectory of the gunshot wound, his bare feet and the possibility the typed the computer message after the killings.

New forensic testimony undermined the certainty of the 1995 evidence, particularly with crime scene contamination and how evidence was being handled.

Despite the defence’s new strategy, the Crown prosecutors stood by their original case:

They continued to argue that only David had the opportunity, means, and technical familiarity to leave the cryptic message on the computer.

They insisted the physical evidence, including David’s fingerprints on the rifle and the bloodstained clothing, still pointed strongly to his guilt.

They disputed the timeline provided by the defence, maintaining that David had time to kill his family before or during his paper run.

After intense deliberations, on June 5th 2009, the jury returned their verdict.

Not guilty.

David Bain broke down in tears while supporters cried, embraced and applauded with a media frenzy exploding outside the courtroom.

To many, this was justice finally served — the correction of a grievous error, and the freeing of a man wrongly imprisoned for over a decade. Campaigners like Joe Karam, who had devoted 13 years to David’s cause, declared it a moral victory.

But not everyone agreed.

Some still believed Bain had gotten away with murder, especially given that "not guilty" is not the same as “proven innocent.” Questions remained, and debates raged in living rooms, courts, classrooms, and Parliament.

The retrial didn’t just clear David Bain — it reignited one of the most polarising criminal cases in New Zealand’s history.